Edith Stein's Reflection on St. Elizabeth of Hungary

II. THE SPIRIT OF ST. ELIZABETH AS IT INFORMED HER LIFE

Why has our time developed such a fondness we might even call it a craze for jubilees? Could it be the oppressive burden of misery that arouses the desire to withdraw again and again for a short breathing spell from the gray, oppressive atmosphere of the present time and to warm oneself a little in the sun of better days? But such flight from the present would be an unproductive way to celebrate jubilees, and we may assume that a deeper, healthier desire, even if not clearly conscious of itself, motivates these glimpses into the past. A generation poor in spirit and thirsting for the spirit looks anywhere where it once flowed abundantly in order to drink of it. And that is a healing impulse. For the spirit is living and does not die. Wherever it was once at work in forming human lives and human structures, it leaves behind not only dead monuments, but leads therein a mysterious existence, like hidden and carefully tended embers that flare up brightly, glow and ignite as soon as a living breath blows on them. The lovingly penetrating gaze of the researcher who traces out the hidden sparks from the monuments of the past this is the living breath that lets the flame flare up. Receptive human souls are the stuff in which it ignites and becomes the informing strength that helps in mastering and shaping present life. And if it was a holy fire that once burned here on the earth and left behind the traces of its action, then all the places and remains of this action are under holy protection. From the original source of all fire and light, the hidden embers are mysteriously nourished and preserved in order to break out again and again as an inexhaustible, productive source of blessing.

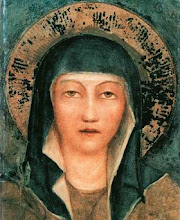

Such a source of blessing is revealed to us in the remembrance the lovely saint who 700 years ago closed her eyes to this world as someone perfected early in order to enter into the radiant glory of eternal life. Her life story seems like a wondrous fairy tale. It is the story of the Hungarian royal child, Elizabeth, who was born in the castle in Pressburg at the same time as the magician Klingsor in Eisenach read of her birth in the stars, and predicted her future fame and meaning for the Thuringia region.(38) The treasures which Queen Gertrud saved up to bestow in splendor on her little daughter sound like something out of A Thousand and One Nights and so also does the vehicle on which all of the splendors were loaded when Count Hermann of Thuringia sent for the four-year-old princess to be fetched to the far-away Wartburg as the bride for his son. The queen even promised to send a large dowry along later. But her relentless striving for riches, glitter, and power came to a sudden end. She was murdered by conspirators, and the child which she had sent abroad to secure a crown became a motherless orphan.

The story of the children Ludwig and Elizabeth reminds us of the intimate relationships in German folk tales. They grew up together, deeply loving each other deeply like brother and sister, and clung to each other in steadfast faithfulness when everything was working to separate them from one another, when everyone gradually turned away from the foreign and unusual child who would rather spend time with ragged beggars than celebrate joyful festivals, who seemed to fit better in a convent than on a royal throne as the center of a luxuriant, radiant life at court, to which the nobility of Thuringia had been accustomed on the Wartburg from the time of Count Hermann.

Then there follows a romance of chivalry, the young count's initiation into knighthood and the beginning of his reign, the glittering wedding and the young wedded bliss of the royal pair, Elizabeth's life as a countess at the side of her husband: festivals, hunts, horseback rides in all directions throughout their land. And placed between all this was her silent concern for the poor and sick in the vicinity of the Wartburg. Then there came the increasing seriousness of a ruler's concerns: her husband's sallies into battle, regency in his absence, struggles against the hunger and pestilence that was bringing down the people, and simultaneously against the opposition of her surroundings that would not permit her to address these needs with all her strength. Finally, there was the Count's crusader vow, the deep pain of farewell and separation, the collapse of the distraught widow when she got the news of her husband's death. A woman's fate like that of many so it seems.

But what happened next is new and has no parallel. She who is sunk in grief raises herself like a mulier fortis [strong woman], as the liturgy of her feast extols her, and takes her fate into her hands. At night during a storm, she leaves the Wartburg where people will no longer permit her to live as her conscience dictates. She seeks refuge for herself and her children in Eisenach, and because she cannot find bearable accommodations, she accepts for the time being the hospitality of her maternal relatives. And even when a reconciliation with the brothers of her husband has come about and she is returned to the Wartburg in utmost honor and brotherly love, she cannot stand it there for long. She must walk the path laid out for her to the end, must leave the place on the heights in order to live among the poorest of the poor as one of them, must place her children into strangers' hands, in order to belong to the Lord alone and to serve him in his suffering members. Stripped of everything, she vows herself to the Lord who gave everything for his own. On Good Friday in the year 1229, she puts her hands on the stripped altar of the Franciscan Church in Marburg and dons the clothing of the Order. She had belonged to it for years already as a tertiary without being able to live by its spirit as her heart desired. Now she is the sister of the poor and serves them in the hospital that she built for them. But not for very long, for only two years later her strength is exhausted and the twenty-four-year-old is permitted to enter into the joy of the Lord.

A life whose outer facts are colorful and appealing enough to arouse fantasy, to awaken amazement and admiration. But that is not why we are concerned with it. We would like to pursue what lies behind the outer facts, to feel the beat of the heart that bore such a fate and did such things, to internalize the spirit that governed her. All the facts reported about Elizabeth reveal one thing, all of the words we have from her: a burning heart that comprehends everything around her with earnest, tenderly adaptable, and faithful love. This is how she put her hand as a little child into the hand of the boy whom the political power struggles of her ambitious parents had given her for her life's companion, never again to release it. This is how she shared her entire life with the playmates of her early childhood until shortly before her death, when her severe director took them from her to dissolve the last tie of earthly love. This is how in her heart she carried the children she bore when still almost a child herself. And when she gave them up, it was certainly out of a maternal love that did not want them to share her own all-too-hard path, as well as a maternal sense of duty that would not let her take away by her own hands the destiny to which their natural circumstances in life entitled them. But she also gave them up because she felt such overwhelming love that they would have become a hindrance in the vocation to which God was calling her.

From earliest youth she opened her heart in warm, compassionate love for all who suffered and were oppressed. She was moved to feed the hungry and to tend the sick, but was never satisfied with warding off material need alone, always desiring to have cold hearts warm themselves at her own. The poor children in her hospital ran into her arms calling her mother, because they felt her real maternal love. All of this overflowing treasure came from the inexhaustible source of the Lord's love, for he had been close to her for as long as she could remember. When her father and mother sent her away, he went with her into the far-away, foreign country. From the time that she knew that he dwelt in the town chapel, she was drawn to it from the midst of her childhood games. Here she is at home. When people reviled and derided her, it was here that she found comfort. No one was as faithful as he. Therefore, she had to be true to him as well and love him above everyone and everything. No human image was permitted to dislodge his image from her heart. This is why strong pangs of remorse overwhelmed her when she was startled by the little bell announcing the consecration, making her aware that her eye and her heart were turned toward the husband at her side instead of paying attention to the Holy Sacrifice. In the presence the image of the Crucified One who hangs on the Cross naked and bleeding, she could not wear finery and a crown. He stretched his arms out wide to draw to himself all who were burdened and heavy laden. She must carry this Crucified One's love to all who are burdened and heavy laden and in turn arouse in them love for the Crucified One. They are all members of the Mystical Body of Christ. She serves the Lord when she serves them. But she must also ensure that through faith and love they become living members. Everyone close to her she tried to lead to the Lord, thus practicing a blessed apostolate. This is evident in the life of her companions. The formation of her husband is a persuasive witness to this, as well as the interior change of his brother, Conrad, who after her death, obviously under her influence, entered an Order. The love of Christ, this is the spirit that filled and informed Elizabeth's life, that nurtured her unceasing love of her neighbors.

We can comprehend Elizabeth's characteristic contagious happiness as arising from the same source. She loved turbulent children's games and continued to take pleasure in them long after, in accordance with the usual ideas of breeding and custom, she was supposed to have outgrown them. She enjoyed everything beautiful. She dressed very well and put on splendid parties that delighted her guests, as was her duty in her position as a countess. Above all, she wanted to bring joy to the huts of the poor. She took toys to the children and played with them herself. Even the sullen widow whom she had for a housemate during the last part of her life could not dim her enthusiasm and had to be pleased by her jokes. And she was moved by the poor to the depths of her heart on that day when she invited them to Marburg by the thousands and singlehandedly distributed among them the remainder of the widow's pension that had been given to her in cash. From morning to evening she walked through the rows giving each one a share. As night came on, many remained who were too weak and sick to make their way home. They encamped in the open, and Elizabeth had fires lit for them. This made them feel good, and songs arose around the campfires. Amazed, the countess listened, and it confirmed for her what she had believed and practiced all her life: "See, I told you that all one has to do is to make the poor happy." That God had created his creatures for happiness had long been her conviction, and she felt it was proper to lift a radiant face to him. And this was also confirmed for her at her death when she was called to eternal joy by the sweet song of a little bird.

Overflowing love and joy led to a free naturalness that could not be contained by convention. How could one walk in measured stride or lisp pretentious speech when the signal resounds before the castle gate, announcing the master's return? Elizabeth forgot irretrievably all the rules of breeding when her heart began beating stormily, and she followed the rhythm and beat of her heart. Again, is one to think about socially acceptable forms for expressing one's devotion even in church? She could only do what love asked of her, even though it produced strong criticism. In no way could she understand that it was improper to take gifts to the poor herself, to speak with them in a friendly way, to go into their huts, and to care for them in their own homes. She did not want to be stubborn and disobedient and to live in discord with her own, but she could not hear human voices over the inner voice governing her. Therefore, in the long run she could not live among the conventional, who could not and would not release themselves from age-old institutions and deeply rooted ways of thinking about life. She was able to remain among her peers as long as a holy union held her fast and a faithful protector remained at her side, sympathetically taking into consideration her heart's command while at the same time prudently considering the demands of the surroundings. After the death of her husband, she had to leave the circles into which she was born and raised and to go her own way. It was a sharp and painful separation, certainly for her as well. But with a heart full of love that was stopped by no barriers separating her from her dear brothers and sisters, she found the path that so many today vainly seek, despite their great good will and the exertion of all their strength: the path to the hearts of the poor.

All through the centuries there runs a human longing that is never put to rest. Sometimes it is expressed softly, at other times more loudly. One who felt it particularly poignantly found a catchy phrase for it: return to nature. And someone who with a consuming longing vainly pursued this ideal his entire life, until he collapsed, has drawn an unusually impressive picture of the person whose every action springs from the depths in a continual motion without reflection or exertion of the will, guided by the command of the heart alone: "one would have the charm of a marionette."(39)

Does St. Elizabeth conform to this ideal? The facts presented so far, pointing to her spontaneous way of doing things, seem to say so. But the sources recount other facts that no less clearly point to a will as hard as steel, to a relentless battle against her own nature: The lovely, youthfully cheerful, enchantingly natural person is at the same time a strictly ascetic saint. Early enough she had to recognize that giving oneself over to the pull of one's heart without restraint is not without its dangers. Extravagant love of her relatives, pride, and greed caused Queen Gertrud to be hated by the Hungarian people, caused her sudden, unexpected death at the hands of murderers. Untamed passion led Gertrud's sister, Agnes of Meran, into a relationship with the king of France that broke up his marriage and brought ecclesiastical censure to all of France. Reckless political ambition entangled Count Hermann in a lifetime of unremitting warfare and left him to die while excommunicated. From time to time Elizabeth even had to see her own husband involved in unjust power struggles and anathematized. And was even she free of these sinister forces in her own breast? By no means! She knew very well that she, too, could not give herself over to the guidance of her own heart without danger.

When, with cunning piety, the child thought up games which would enable her to skip off to the chapel or throw herself down secretly to say her prayers, a mighty tug of grace must certainly have been working in her heart; but she could have suspected, too, that in her play she was also in danger of getting lost from God. This becomes even clearer when the young lady came home from her first dance with a serious face and said, "One dance is enough for the world. For God's sake, I want to forego the rest of them." When she arose from her bed at night and knelt to pray or left the room entirely to let the maids whip her, this surely tells us not only of her general desire to do penance and to suffer voluntarily for the Lord's sake, but that she wanted to save herself from the danger of forgetting the Lord while at her beloved husband's side. Surely Elizabeth's natural sense of beauty was drawn to pretty children rather than to ugly ones, and was repelled by the appearance and odor of disgusting wounds. Therefore, since she repeatedly sought out such ailing creatures to tend to them herself, this tells not only of her compassionate love for the poorest, but also of the will to overcome her natural revulsion. Even during the last years of her life Elizabeth prayed to God for three things: for contempt for all earthly goods, for the gift of cheerfully bearing humiliation, and to be free of excessive love for her children. She could tell her maids that she was heard in all of this. But that she had to ask for these things showed they were not natural for her, and that she had probably been struggling for them in vain for a long time.

Forming her life to please God Elizabeth strives for this goal not only for herself and in battle against her own nature. With full awareness and the same inflexible determination, she endeavors to influence her surroundings. As countess she takes pains to counteract excesses in sumptuous clothing and to move the titled ladies to renounce this or that vanity. When she begins to avoid all food obtained with illegal revenues and is thus often forced to go hungry at the fully-laden royal table, she assumes that her loyal companions Guda and Isentrud will share her deprivations, as later they will also follow her into the distress of voluntary banishment and poverty. And what a protest this abstention from food was against the whole way of life around her!

Her increasingly austere way of life made most severe demands on her husband. He had to look on while she treated herself with the utmost harshness, endangered her health, squandered his wealth lavishly; while, by all this, she roused the opposition of his family and of all at court; and, finally, while she fought to detach herself interiorly from him, even bemoaning bitterly that she was bound by her marriage. All this required heroic self-mastery on his part as well, and one readily understands why, as he accepted everything with love and patience, faithfully taking the trouble to stand by his wife in her striving for perfection, the young count came to be regarded as a saint by his people.

Initially, it was probably the doctrine of the Gospel and the general ascetic practices of her time that guided Elizabeth in her striving for perfection. Every now and then she had an insight and sought to put it into practice. When the Franciscans came to Germany, she found what she was looking for, a clearly outlined ideal and complete way of life; and, as her guest on the Wartburg, Rodiger instructed her about the lifestyle of the Poor Man of Assisi. Now suddenly she knew precisely what she wanted and what she had always longed for: to be entirely poor, to go begging from door to door, to be no longer chained by any possessions or human ties, also to be free of her own will to be entirely and exclusively the Lord's own. Count Ludwig could not bring himself to dissolve the marriage bond, to let her leave him. However, he would help her toward a regulated life, approximating her ideal as closely as possible. It was probably better for her guide not to be a Franciscan otherwise her unfulfillable wishes could not be put to rest but someone who dampened her excesses with quiet reason and yet had an understanding of her interior desire. Such a man was Master Conrad of Marburg who was recommended to the count as a guide for his wife. He was a secular priest but as poor as a beggar monk, entirely consecrated to the service of the Lord, and very strict with himself as well as with others. This is how he traveled throughout Germany as preacher of the crusade and warrior for the purity of the faith. Elizabeth took a vow to obey him in the year 1225 and remained under his direction until her death. For her to submit herself to him and to continue submissive to him was surely the severest breaking of her own will, for, in accordance with her own wishes, he not only engaged in the severest battle against her lower nature, but also directed her love of God and neighbor in directions different from her impulse. Neither before nor after the death of her husband did he ever permit her to give up all her possessions. He restrained her indiscriminate almsgiving, gradually limited it and finally completely forbade it to her. He also tried to keep her from tending people with contagious diseases (the only point on which Elizabeth had not entirely submitted by the end).

Certainly his ideal of perfection was not inferior to hers. It was clear to him from the beginning that he was entrusted with the guidance of a saintly soul, and he wanted to do everything he could to lead her to the summit of perfection. But his opinions about the means thereto differed from hers. In the first place, he wanted to teach her to strive for the ideal where she was, just as he had not considered it necessary to enter an Order himself. So he permitted her to join the Franciscans as a tertiary and interpreted for her the vows in a way appropriate to her state in life. As long as her husband was living she was to perform all her marital duties, but to renounce remarriage if he died. She was to live a life of poverty but not carelessly squander what she had, rather providing sensibly for the poor. Foremost in this life of poverty was the food ban, that prohibited her all nourishment not obtained from lawful revenues. Carrying out this prohibition (according to recent research) is said to be what caused her to leave the Wartburg after the death of her husband. It is assumed that her brother-in-law, Heinrich Raspe, was unwilling to tolerate her absenting herself from the royal table, and cut off her widow's pension to coerce her (surely also to put an end to her wasteful good deeds). After the extreme need and abandonment that she suffered from this voluntary or involuntary banishment, she could not bear to become reaccustomed to her former circumstances. She only returned to the Wartburg temporarily after her reconciliation with the count's family and immediately began to discuss with Master Conrad the best way of realizing her Franciscan ideal. He agreed to none of her suggestions, allowing neither entrance into a convent nor the assumption of a hermit or beggar life. He could not prevent her from renewing her vows or from allowing herself to be clothed in the dress of the Order. And he let her take up residence in her city of Marburg where he lived, too. He determined a lifestyle for her in accord with his judgment, by using her means to build a hospital in Marburg and assigning her certain duties in it. It was probably her own idea not to use any of her income for herself, but to earn her subsistence by her own hands (by spinning wool for the Altenburg monastery), and her director agreed. In Master Conrad's opinion, the most difficult and important task was to teach his charge obedience. It was his pious conviction that obedience was better than sacrifice, that there was no way of attaining perfection without letting go of all of one's own wishes and inclinations. And his enthusiasm for his goal drew him into corporal punishment when she repeatedly overstepped his orders. Certainly, deep within Elizabeth agreed with him. This is evident not only by the patience and meekness with which she bore these severe humiliations. She would certainly not have conceded on such an essential point as the renunciation of her greatly desired lifestyle if she had not been convinced of the importance of obedience. She saw God's representative in the director given to her and whom she had not chosen herself. More unerringly than the tug of her own heart, his word disclosed God's will. In the last analysis, it finally comes down to one thing: forming one's life according to God's will. Thus, they both wage a relentless struggle against natural inclinations.

Sometimes it is Elizabeth herself who takes the lead and finds only the master's approval, as in the move to Marburg and the separation from her children. Sometimes Conrad commands and Elizabeth submits obediently to him, e.g., when he takes away the beloved companions of her youth and substitutes housemates that are hard to bear, when he increasingly restricts her joy of personally giving alms and finally entirely prohibits it. There was only one point on which she would not totally concede. Along with her service at the hospital, she insisted on continuing to have with her a child sick with a particularly unbearable illness in her own little house next door and to care for it all alone. A little fellow ill with scabies even sat beside her death bed, as Master Conrad himself told Pope Gregory IX, who had entrusted to him the care of the widow after the death of the count. Immediately after her death, Master Conrad enthusiastically urged Pope Gregory to beatify her.

So we seem to get a conflicting picture of the saint and the formation of her life. On the one hand we have a stormy temperament that spontaneously follows the instincts of a warm, love-filled heart uninhibited by her own reflection or outside objections. On the other hand we see a forcefully grasping will constantly trying to subdue its own nature and compelling her life to conform to an externally prescribed pattern on the basis of rigid principles that consciously contradicted the inclinations of her heart.

However, there is a standpoint from which the contradictions can be understood and finally harmoniously resolved, that alone truly fulfills this longing to be natural. Those who avow an "unspoiled human nature" assume that people possess a molding power operating from the inside undisturbed by the push and pull of external influence, shaping people and their lives into harmonious, fully formed creatures. But experience does not substantiate this lovely belief. The form is indeed hidden within, but trapped in many webs that prevent its pure realization. People who abandon themselves to their nature soon find themselves driven to and fro by it and do not arrive at a clear formation or organization. And formlessness is not naturalness. Now people who take control of their own nature, curtailing rampant impulses, and seeking to give them the form that appears good to them, perhaps a ready-made form from outside, can possibly now and again give the inner form room to develop freely. But it can also happen that they do violence to the inner form and that, instead of a nature freely unfolded, the unnatural and artificial appears.

Our knowledge is piecemeal. When our will and action build on it alone, they cannot achieve a perfect structure. Nor can that knowledge, because it does not have complete power over the self and often collapses before reaching the goal. And so this inner shaping power that is in bondage strains toward a light that will guide more surely, and a power that will free it and give it space. This is the light and the power of divine grace. Mighty was the tug of grace in the soul of the child Elizabeth. It set her on fire, and the flame of the love of God flared up, breaking through every cloak and barrier. Then this human child placed herself in the hands of the divine Creator. Her will became pliant material for the divine will, and, guided by this will, it could set about taming and curtailing her nature to channel the inner form. Her will could also find an outer form suitable to its inner one and a form into which she could grow without losing her natural direction. And so she rose to that perfected humanity, the pure consequence of a nature freed and clarified by the power of grace. On these heights it is safe to follow the impulses of one's heart, because one's own heart is united with the divine heart and beats with its pulse and rhythm. Here Augustine's astute saying can serve as the guideline for forming a life: Ama et fac quod vis [Love and do what you will].

1 Comments:

What a magnificent commentary by one saint about another! It lifts one out of this world! As a Carmelite tertiary, I have devotion to both St. Teresa Benedicta, Carmelit martyr, and St. Elizabeth, patroness of tertiaries. May God reward you for sharing such beauty!

Post a Comment

<< Home