Before I branch out and do some profiles on non-Poor Clare monasteries, I wanted to do the Poor Clare Colettines some justice and provide you with the text from their vocation booklets. Even if you don’t have any intention on becoming a Poor Clare or entering the religious life, I highly recommend that you read it. The following overview of their cloistered vocation and how their lives are an act of love for us in the world explains in part why I love the Poor Clares so much and why I dedicate so many posts on this blog to them! You’ll also enjoy the following excerpt because it was written by the late Mother Mary Francis, one of the most exceptional Poor Clare Colettine authors!

The Cloistered Poor Clare Nuns

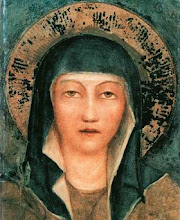

by Mother Francis, PCC, Abbess

Monastery of Our Lady of Guadalupe

Roswell, NM

Perhaps no life has been more subjected to misinterpretation than the cloistered contemplative life. A cloister is variously thought to be: a haven for those unfit to live in the world; a refuge for the frustrated; a sinecure for those unwilling to take on the burdens of the active apostolate.

A Poor Clare monastery is decidedly none of these. The nuns are called Poor Clares because they are poor, living by the work of their hands and their minds and on the alms of the faithful, and because they are followers and daughters of one of the most charming women who ever lived. Her name was Clare. Clare of Assisi.

The whole testament of history proves that no enduring work of a great man is begun or fulfilled without the cooperation o a great woman. And no woman ever appreciated the ideals of a great man more profoundly and comprehensively than St. Clare understood the ideals of St. Francis of Assisi.

In a medieval society that was suffocating in the close quarters of materialism and gagging on surfeit, Francis came preaching the beauty of evangelical poverty. Clare listened.

Into the chaos of unending wars and petty rivalries, the "little poor man of Assisi," as he came to be called, brought this gentle benediction: "May the Lord give you peace."Clare understood.

Where ambitions seethed and men were ruthless in their quest for power, Francis begged as a favor to be considered the least of men. Clare caught his inspiration.

Like the Divine Child held in the arms of old Simeon and prophesied to be a sign of contradiction Francis of Assisi came with a form of life that cut through the morass of war and hatred and worldliness. He walked at right angles to all that characterized his age. He was a sign of contradiction.

Clare was seventeen when she heard Francis preach of the love of God and evangelical poverty with such burning sincerity that the richest young man in Assisi promptly gave away his fortune to the poor and ran after him, that a scholar and canon came to learn a better wisdom from Francis, and that glittering knights threw down their swords to take up the weapons of God as Francis taught them.

It was the beginning of the Franciscan Movement of the thirteenth century and the inauguration of the Franciscan Order, which is the largest in the Church today and which God himself promised Francis would endure to the end of time.

But what of Clare? She was beautiful. She was rich. She could not preach with Francis in the streets. She could not beg her bread from door to door as his followers did. She could not be a sign of contradiction to the world in the same manner that he was. So Clare went to him and told him of God;s summons in her soul, asking him what to do. Francis told her. And that was the beginning of his Second Franciscan Order, the cloistered Poor Ladies who were later to be known familiarly as the Poor Clares.

Why did Assisi's loveliest debutante of 1212 want to lock herself up in a cloister? Why did laughing, singing, sought-after Clare want to live in silence and prayer? Why did a girl whose home was a castle desire to be poor, to live by the work of her hands and the alms of the faithful?

What the world calls "everything," Clare assuredly had. It was not enough. Her heart was too great to be filled with less than the whole. She simply plunged herself into the Heart of God. There she could fulfill her destiny. There she would be another sign of contradiction to those who look for happiness everywhere except in God.

Clare was scarcely a social misfit. She was definitely not neurotic, nor was her pretty sister, Agnes, who became her first follower. It required an extraordinary fortitude for two thirteenth-century girls to stand firm against their raging relatives, their indignant friends, their baffled suitors. It takes the same courage today, not to "talk down," but to live down the objections of those who demand that talented young girls do something more "useful," than loving God and being His immediately, directly and utterly.

Certainly Clare was not a frustrated young woman. She could have had everything the world calls good, but it was not good enough for her. She preferred what God calls everlasting good and realized her own full capacities as so great a woman could never otherwise have done.

Lazy? A cloister sinecure? Clare had grown up surrounded by servants, but she wrote in her Rule that her nuns were to consider work as "a grace." And they were expected to use the grace persistently.

The closer a soul draws to God, the more entirely she is dedicated to Him, the more she radiates God. The poet has declared that Our Lady "had this one work to do / let all God's grace shine through."

So has the contemplative Poor Clare. Her mission is to be God's, to let Him shine through her on all the darkness of misery which shrouds the world. And as in St. Clare's age, so in our own, people understand this without any need to reason about it - the common people, the suffering, the sinners.

They flock to Clare's poor little monastery in the thirteenth century to ask her prayers for their sick, their prodigals, and their friends. In our century, the monastery doorbell is rung by the lonely, the discouraged, the despairing. The monastery mailbox holds wistful appeals for compassion and understanding pathetic confessions of mistakes.These people take it for granted that the Poor Clares, cloistered from the world, are closer to its heartaches and miseries than any others simply because they live hidden in the embrace of God.To understand the contemplative vocation properly is to know that its apostolate is universal and timeless.

The Poor Clare has stepped apart from the world and has thus got a better perspective on it. She has left the world not because she hates it, but because she wants to love more purely and more realistically.Not only the wars of nations and the scourge of evil leaders of men are her concern, but the small bickerings that threaten the peace of the family down the street.She does not beg the light and grace of the Holy Spirit only for the workings of the United Nations, but for that one little boy in Schenectady whose mother is worried that he may flunk in arithmetic.

St. Francis of Assisi was a great contemplative but God asked him to sacrifice his live of silence and retirement to preach the Gospel, to let his contemplation overflow into his active apostolate. St. Clare of Assisi had a burning missionary heart, but God asked her to channel all its energies into the love and reparation of the cloister.

Her mission field was the whole world, though she would never see the world. Together their lives were a unit, and each the perfect complement of the other. It needs a great heart to fashion a contemplative, a capacity for love so wide and deep that only God can fill it, a missionary zeal so ardent that no fewer than all the souls in the world can satisfy it.

Christian motherhood and consecrated virginity form a marvelous entity. Each is a fulfillment, and each a symbol. The Sacrament of Matrimony symbolizes the union of Christ with Holy Church. Consecrated virginity symbolizes the union of Christ with the souls of the blessed. Each is a positive thing, and virginity is no more a mere negation of motherhood than human maternity is a mere negation of virginity.

A Poor Clare understands that her solemn vow of chastity is not just a pledge to abstain from the pleasures of carnal love, nor a promise to refrain from normal affective fulfillment, but a positive flaming, soaring commitment of her womanhood to a Divine Lover.

Because her consecrated virginity lifts her to a plane above carnal love, her affective responses are only the more tender for being the more purified. Womanhood is fulfilled quite as perfectly in a life of virginal chastity as in human marriage. And that is why the Church's ancient and elaborate ceremonial for the consecration of virgins has for its climax the placing of a wedding ring on the finger of the newly professed nun. "Receive this ring that marks you as a bride of God." She is wedded to Christ.

And the union is fecund with souls.The cloistered Poor Clare is destined for the spiritual maternity of countless souls. The more perfect her life of love and reparation, the more fruitful is her motherhood of souls. Consecrated virginity generates tenderness and compassion beyond what carnal love can attain, simply because it is not limited. Virginal love partakes of the boundlessness of Christ's love for souls. A Poor Clare's Divine Lover has a heart of infinite Love. It is to be expected that her own capacity for love will go on increasing as she grows in union with Him.

There is nothing stifling to the human personality in consecrated virginity. The Poor Clare's vow of chastity is not only an oblation, but also a sublimation. Her love is released on a plane above the relations of conjugal love in spiritual maternity. Her ambition is to mother all the souls in the world.

Postulants are received between the ages of eighteen and thirty, with exceptions sometimes made where there is good reason. Experience has long proved that any normal woman of average strength and good health, free from disease or serious physical defect, can observe the Rule of St. Clare without detriment to her health. Indeed, the regularity of the life in including simple foods and outdoor work is conducive to good health.

A high school education is required. A college education or experience in some specialized work can be an asset. No financial dowry is required, as this was never the mind of St. Francis or St. Clare; but a young woman is expected to bring the clothing and small accessories she will need as a postulant, if she is able to do so.

No one is ever refused admittance for lack of means, but postulants are to bring a willing heart, a teachable mind, and a pliable character. These are the desirable dispositions. Progressively to fathom the contemplative vocation requires the full effort of mind, heart and will. The ability to be taught is of itself a talent - meant to be multiplied.

What stirs in the heart of a young woman called to the cloister? Or, how does she know she is called? The answers are as numerous and varied as those who are called. Maybe she read about the Poor Clares. Perhaps she visited at the parlor grille of a monastery, or saw a Profession ceremony.

It may have been that she knelt in the public chapel and heard the chants of the Liturgy of the Hours, the Divine Office, flowing on and on in a river of prayer. Or, it may be that she knows next to nothing about the Poor Clares. And yet that small insistence in the soul remains. I? Impossible! Or -- is it?

A vocation is a free gift of God. It is offered, not forced. God invites, but He does not compel; and eternity will reveal how many vocations have been lost or disregarded. The rich young man in the Gospel was assuredly called, but he did not respond. He had a vocation, but he chose not to follow it. The Gospel says that ". . .he went away sad." (Mt. 19:22). Doubtless he remained sad for the rest of his life.

How does one protect her vocation? Obviously, only with the strength of Christ who is offered daily on the altar at Holy Mass, only with the Bread of the strong which is Holy Communion. God does not choose a young woman because she is good, but because He is so good. The one who thinks herself qualified to be a great success in the cloister is probably the one who will fail, whereas the one who is confused and humbled at the idea that God should look towards such poor material as herself for the fashioning of a contemplative nun is likely to persevere.

"The wind blows where it wills, and you can hear the sound it makes, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes; so it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit." (Jn. 3:8). God is the master of His works and His plans. Often we cannot know what He is doing or why He is doing it. But He knows. It is enough to be convinced of that, and to listen for His voice. Listening is a great and delicate art, and scarcely to be learned in the midst of clangor.

The Holy Spirit speaks in a whisper. It is all too easy to drown out His voice, but in the quiet watches of the soul, His invitation is heard.

"Giving the bud, I give the flower." St. Clare love to call herself the "little plant" of St. Francis. Each postulant is a new little plant of Francis and Clare. She is part of the perennial springtime of the Franciscan order, and in her religious life the Franciscan ideal will have one more flowering."And not only about us did our most blessed Father prophesy those things, but also about the others who were to come afterwards in the holy vocation in which the Lord has called us," declared St. Clare. From heaven, her watchful love beams down upon her youngest daughters, her new postulants.

When St. Clare left her castle home in the blackness of night that Palm Sunday of 1212, she was setting out to become the first of St. Francis' "Poor Ladies," nuns dedicated to a life of prayer and penance, nuns most intimately united with the Divine Lover in the silence of the cloister. She dressed for the occasion. For such a bridegroom, she wore her finest gown, the rarest of her many jewels. And then, because they were only symbols of reality, she cast them all away. Francis cut her lovely hair, preserved to this day in the precious reliquary in Assisi. The tangled silken ropes of that long hair give their mute testimony to holocaust: her crowning glory laid down at the feet of her Prince.

Postulancy in the Order of St. Clare today is a year of preparation for that kind of total giving which will be climaxed in solemn Profession some six years later.

The noviceship of one or two years which follows upon postulancy is a time of refining and deeper evaluation, of profounder preparation and expectation. Now the life of prayer and penance is embraced in fuller detail. And because a life of prayer and penance is a life which generates joy and peace which the world cannot bestow or understand or take away, the day that a postulant assumes a more specifically religious garb similar to that of the professed nuns and becomes a novice, is a day of special rejoicing in the monastery. The Order of St. Clare has one more young penitent eager to give herself to God and to spend herself for souls.

Why was Christ crucified? For the love of mankind. For the same reason, the Poor Clare dedicates herself to a life of prayer and penance. By a strange irony, pleasures quickly turn to ashes, and leave only sorrow and frustration in the heart, but sacrifice spreads a perfume of joy in the soul and over the world.

During the time of noviceship, the young Poor Clare is preparing for the great day of her vows. She learns the enduring paradoxes of religious life: how one must lose one's life to find it, be humbled in order to be exalted, become as a little child to reach spiritual adulthood. The springtime season looks always to the summering of the fuller commitment which is the making of temporary vows.

"Christ has set a seal upon my face that I should admit no other lover but Him," sings the young professed Poor Clare. First Profession of vows is made for a period of three years; but in the heart of Christ's bride, it is already made forever. No one makes provisional offering of herself to God. No one promises to be His - for awhile. Holy Church wisely legislates that temporary vows precede the total commitment of the religious by solemn vows, but she does not legislate for the heart. The young professed is free to whisper to Christ in the inner court of her being, "Forever!" On the day of her solemn vows, she will make this a public declaration to be accepted and sealed by the Church.In exchanging the white veil of the novice for the black veil of the professed nun, the young Poor Clare assumes her full responsibilities as a member of her Order: prayer, penance, the spiritual motherhood of souls.

The vows bring a marvelous enrichment. One is truly bound to Christ now with a fourfold and very dear covenant. To the ordinary three vows of religion, the cloistered Poor Clare adds a fourth, that of enclosure. She promises to live in obedience, in poverty, in virginal chastity, and in enclosure.

Some monasteries have extern sisters to whom is entrusted the outside business of the community and who are permitted to leave the monastery when it is necessary. These do not make the vow of enclosure although they are the special guardians o the cloister by the dedicated and self-sacrificing service they render, and they share fully in the family life of the community. In other monasteries, the external business of the door and telephone is attended by cloistered nuns appointed for this task, as is provided by the Church.

Separated from the world, the Poor Clare is in a better position to love it selflessly and to compassionate its miseries. She has a spiritual perspective on suffering and on souls. And, as the bride of Christ, she has direct access to His listening ear. Being entirely His, she knows He is entirely hers.She prays with the complete confidence of one loved, cherished, chosen. She has enriched her own womanhood by the act of oblation, and is secure in the possession of a Lover more beautiful than all the sons of men.

And Christ is a Lover who will never fail her, never desert her, never grow tired of her. Unlike a woman entering into human wedlock, the novice making the marriage vows of religion can perfectly forecast the future as far as her Bridegroom is concerned. He will be forever faithful, loving, devoted to her. With His grace, she will be so to Him. And out of this union of God and creature will issue blessings for all the world.

For many persons, the day ends when they retire at midnight. For Poor Clares, the day begins when they rise at midnight.The first of the canonical hours of the Divine Office is chanted at midnight while the world around is sleeping or perhaps sinning. Sin loves the cover of night. Prayer goes out into the backstreets of the night to seek out sinners and reclaim them. The night Office is a torch held in the hands of the Poor Clare as her love goes looking down the lanes of the world for the lost, the straying, the despairing, the suffering, the dying.What is this Divine Office, of which the midnight prayer is the first hour? Even among the laity, the breviary is today regaining its place of honor, the place it held in medieval times when kings and queens retired to their private chapels to read it, or generals of armies paced up and down as they recited it before battle.But it is to her priests and contemplative nuns that Holy Church entrusts the Liturgy of the Hours of the Divine Office to be recited officially in her name. Thus Pope Pius XII, in his Apostolic Constitution Sponsa Christi, said: "The Church deputes nuns alone among the women consecratated to God for the public prayer which is offered to God in her name. . .and these she binds under grave obligation by law according to their Constitutions to perform this prayer by reciting daily the canonical hours."

Dom Columba Marmion has written powerfully of the grandeur of this Divine Office, explaining how all things are of value only in such measure as they procure God's glory. And while some works, such as literary work, teaching, sweeping, cooking, nursing, working in the garden, have no direct relationship with God's glory, although they give Him glory indirectly when transformed by the love and the intention of the one who performs them, there are other works which procure God's glory directly. "Such," says Dom Columba, "are Holy Mass and the Divine Office. From God's point of view, these works surpass all other works." It is to them that Poor Clares are primarily dedicated.

The work which re-creates a nun for more prayer is also the complement of prayer which ennobles and gives significance to her work. Whether she bakes bread or writes books, sweeps the cloister or paints in oils, patches habits or plays the organ, the Poor Clare strives to remain united to God. All or any of these works have meaning only insofar as they are the functions of her obedience, the sacrifice of her hands or mind, the overflow of her prayer. "The prayer of an obedient person," said St. Colette of Corbie, "is worth more than one hundred thousand prayers of a disobedient one."It is thus that a basketful of weeds pulled up from the cloister garden may shine as gold and curl as incense in the sight of the Lord.The Poor Clare works because she is poor, and the poor must always work hard. She works because she is obedient, and all her works are given to her in obedience. She works because she is vowed to chastity, and work is the safeguard of chastity.She works because she is enclosed to pray for the world and to do penance for the world. Ad she knows that work was the first of the penances imposed by God on fallen man. "By the sweat of your face shall you get bread to eat." (Gen. 3:19).The Poor Clare is glad to do so; and what her own works will not supply, she knows that the alms of the faithful who understand her life will supply. "Let them confidently send for alms," wrote St. Clare in her Rule. "Not should they feel hesitant, since the Lord made himself poor in this world for us."It is a hidden life, this life of the cloister. It is a replica of the life of the God-Man who for thirty years worked in a carpenter shop and prayed on the mountaintop. And that is why the contemplative life is at once the most limpidly simple of all lives, and the most mysterious. The idea of work being "a grace" was a novel one in St. Clare's thirteenth century. It is more novel in our century. A thousand labor-saving devices, bewildering arrays of switches, push buttons, and foot pedals seem to be constituted to abolish work. Shorter hours, higher wages, compensations.

The Poor Clares would like longer hours for accomplishing all the works of a monastic labor schedule. Wages? St. Francis was mockingly asked to sell a drop of his sweat. The Saint smilingly refused the prospective buyer, saying that his sweat was already sold to God for a very great price.Compensations? An eternal reward for the small work done in obedience could not be considered meager. And work is itself a reward. Work is good. Work is a grace. To season both prayer and work, there is the daily hour of recreation.

Mother Mary Francis, PCC